Author: Vitālijs Rakstiņš Defence Counsellor, Embassy of the Republic of Latvia to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Latvia

The last years have made resilience the buzzword, starting from the Recovery and Resilience Facility and resilience basket in the European Strategic Compass, ending with 2021 NATO summit resilience commitments as one of the key deliverables[1]. The resilience is also regularly mentioned in national security planning documents, such as the Latvian State Defence Concept and National Security Concept[2], or in the British Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy.

One of the freshest definitions of resilience is in the new directive of the European Union on the resilience of critical entities, which defines resilience as the ability to prevent, resist, mitigate, absorb, accommodate to and recover from an incident that disrupts or has the potential to disrupt the operations of a critical entity. A common definition of resilience usually consists of three main elements:

- preparedness/ prevention,

- ability to resist/ mitigate

- ability to adapt[3] and recover,

National resilience is the sum of all factors, including effective and trusted governance, government capabilities, social cohesion, and individual and business resilience.

[2] Game changer

The unprecedented spread of the COVID-19 outbreak worldwide severely tested national resilience. Many governments underestimated risk early and failed to execute timely measures to stop the spread of infection, and overreacted later often employing measures balanced on the edge of legal. The crisis proved the growing importance of the private sector in national security. In emergencies, every entrepreneur becomes a part of national security by executing government orders and introducing safety/security protocols (for instance, social distance restrictions in his premises); and manufacturing goods or providing services critical for the population.

Disruption of global supply chains exposed dependencies on few international suppliers and stressed the need of robust and shorter supply chains to enhance the resilience of essential service providers. Critical shortages in protective gear and medical equipment, raw materials and vital goods pressed states to intervene in the market, setting export restrictions and war-like mobilizing economies, overtaking critical goods and sometimes using wartime legislation to manufacture certain goods. When states set export restrictions, closed borders and ground aviation, the just-in-time business model faced a shortage of goods and raw materials. In short, not governments, not the private sector, not civil society, was ready for such pandemics.

[ 3] All-Hazard approach / Whole-of-threat approach

We are living in a time when tragic natural or human-made disasters are becoming daily news. COVID-19 is unlikely to be the last global crisis. Quoting the NATO 2021 summit’s resilience commitment – “we are addressing threats and challenges to our resilience from both state and non-state actors, which take diverse forms and involve the use of various tactics and tools. These include conventional, non-conventional and hybrid threats and activities; terrorist attacks; increasing and more sophisticated malicious cyber activities; increasingly pervasive hostile information activities, including disinformation, aimed at destabilizing our societies and undermining our shared values; and attempts to interfere with our democratic processes and good governance”. A new all-hazard approach to emergency management should be introduced, recognizing common elements in managing responses to virtually all emergencies. Up to 80 per cent of the consequences of different hazards are more or less similar (for instance, no electricity, no communications etc.). It is impossible to predict or prevent every risk to national security. Still, general readiness to all-hazard situations and comprehensive training to address different scenarios is the only realistic option to enhance resilience.

[4] whole-of-society approach

No government possesses a full spectrum of capabilities required to deal with complex, emerging, multidimensional security threats. COVID-19 is an example. On the other side, the responsibility for ensuring safety and security lies not solely with the government but with the state as a whole. Individuals, businesses and organisations all play a part in building national security and resilience. Active participation of citizens is crucial in the context of increasing uncertainty of the security environment and the emergence of new threats. COVID-19 crisis was an eye-opener for those who forgot that every single person has responsibilities. A whole-of-society approach is an integrated approach, bringing together all levels of government, essential service providers, the wider private sector and civil society. COVID-19 is an example of the necessity of a genuine partnership between the state and private sectors, starting from risk assessment and planning to joint exercising/training.

[5] Continuity of Essential Services

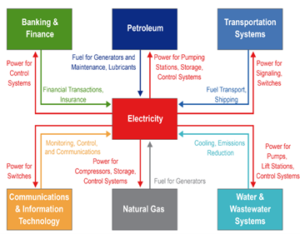

COVID-19 also exposed the importance of continuity of essential services/function, including essential personnel. Even during the most severe COVID-19 lockdowns, travel bans and curfews, essential personnel was exempt from restrictions and ensured essential functions of both public and private sectors. In any crisis, essential services (such as electricity, communications, financial services, medicine etc.) must be provided at least at the minimal pre-defined level. If essential services are provided during the disaster, then all other vendors will be able to operate, and the economy will not stop. Ensuring business continuity of power stations, communication operators, and hospitals is also critical for national defence because armed forces heavily depend on essential services[4].

Another challenge is the mutual interdependency of essential services, which could lead to cascading disruptions. For example, a blackout could impact communication and finance services, which could affect other essential services. The only solution is joint cross-sectoral planning and mutual trust, improving the resilience of all ecosystems.

We are witnessing the shift from kinetical and non-kinetical protecting critical infrastructure to focusing on the resilience of services and the ability to operate during a disaster. For instance, the European Union initiatives like the CER directive or NIS2 directive[5]; or legal framework to minimize strategic dependencies like the 5G toolbox or Critical Raw Material Action Plan. Part of the security of essential services is screening foreign direct investment and control of intellectual property/patents.

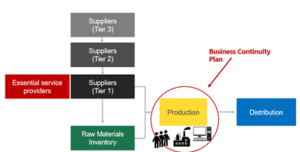

[6] Business Continuity

International Standardization Organization (ISO) standard ISO 22301:2019[6] defines business continuity as a holistic management process that identifies potential threats to an organization and the impacts to business operations those threats, if realized, might cause, and which provides a framework for building organizational resilience with the capability of an effective response that safeguards the interests of its key stakeholders, reputation, brand and value-creating activities. Several international standards focus on risk management and business continuity, others focus on sectoral security, for example, ISO 27000 family of information security standards.

Nevertheless, there are no internationally recognized ISO-type standards to prepare the industry for military aggression, gray zone warfare, or unknown unknowns contingencies (for instance, space weather). Each year, more private companies are targeted by hostile actors both in the kinetic and non-kinetic ways (cyber attacks) as part of ongoing hybrid or gray zone war. And not always insurance covers such attacks (if recognized as state action /act of war). The majority of companies are small-medium enterprises (SME) lacking resources to create holistic security and business continuity plans[7] to address all emerging threats. A new comprehensive business continuity planning system of essential services was introduced in Latvia. The Latvian government has prepared a regulatory framework (checklists) on creating a resilient business continuity system to address whole-of-threats[8]. All essential services providers must introduce a resilient business continuity system, but every interested SME is encouraged to develop business continuity using the publicly available methodology.

[7] Just-in-time / Security of Supply

Nowadays, most businesses use a so-called just-in-time business model with minimal inventory in warehouses and total dependency on logistics. To become resilient, the company needs to review its supply chain (multivendor policy, short and transparent supply chains) and introduce a just-in-case business model, stockpiling some reserve inventory or raw materials. Resilience is also a competitive advantage because also during a disaster, companies are interested in getting revenue. For instance, during the pandemic, companies who were able to rapidly change their business model and introduce safe and secure services could continue operating with good profit.

COVID-19 exposed vulnerabilities of extended supply chains involving different suppliers. Nowadays, the disruption of logistic chains becoming a new normal, starting with the blockage of the Suez Channel by Evergreen container ship ending with the recent closures of the biggest Chinese ports because of COVID-19. Disruption of the supply chain could also cause domestic factors; for instance, in August 2021 UK government considered the army’s involvement to ensure logistics of food retailers as there was a gap in 100,000 lorry drivers. Security of Supply is now a concern of any entrepreneur.

[8] Cognitive Resilience

COVID pandemic also spotlighted the need for psychological defence or using modern wording – cognitive resilience. The unprecedented spread of misinformation about virus and vaccination, often called infodemic, is a global problem. In some nations, untrust in government abilities to address the outbreak ended with panic buying at the pandemic’s beginning. Untrust in government and science also raised protests against restrictions and vaccination. Western societies are divided as never before, which will have a long-term impact.

COVID-19 exposed existing vulnerabilities in our societies – lack of media literacy, critical thinking, digital hygiene, lack of trust in authorities etc. But the same vulnerabilities are regularly abused by hostile actors, executing information and psychological operations against western societies.

Government has a role and toolbox to counter hostile actions (blocking homepages, withdrawing broadcasting licences etc.) and to educate the community (media literacy, digital hygiene and critical thinking). But, it is always an individual decision to use this knowledge or live in the information bubbles.

[9] New Normal

Like 9/11 changed our lives forever, COVID-19 the same. We cannot avoid emerging risks, and the only strategy is to change the mindset of the decision-making process, making it risk-informed. At the beginning of pandemics, it seemed that national security ecosystems would be fundamentally transformed. Unfortunately, after almost two years of pandemics, there are only minor changes. The public and private sector adopted to live with pandemics, but still not ready to all-hazards. Nevertheless, recent natural disasters and consequences of climate change, ongoing wars, and constant gray zone aggression is a wake-up call to enhance individual, community and national resilience:

Individual preparedness to all-hazards is a common concept of individual and community readiness to different disasters, usually titled “72 hrs” (ability to survive at least for 72 hours). Individual preparedness is also about psychological readiness and cognitive resilience (including media literacy, critical thinking, cyber hygiene etc.) Everyone nowadays is a crisis manager, assessing informed risk made decisions every day (for example, a simple commute nowadays is a serious risk assessment).

The private sector’s resilience: it’s about business continuity planning and, for some essential service providers, a business model driven by national security demands. The private sector is part of the national security system and needs to be trained and educated. Nowadays, many companies are already involved in national security, like critical infrastructure. This trend is expanding because many businesses nowadays have to implement epidemiological security protocols, screen suppliers and customers (for instance, checking sanction lists, counter-terrorism financing etc.) de facto creating simple KYC (Know Your Client) protocols for SMEs. They are becoming a fundamental part of the national security ecosystem. At the same time, the resilience of businesses could be part of their competitive advantages.

State readiness: lessons learned from COVID-19 will impact national strategic reserve systems and contingency plans. Currently, many nations are reviewing their risk registers and crisis management systems to prepare for the next crisis. Unfortunately, the government’s heavy involvement in COVID-19 pandemic management often gives an illusory sense of preparedness to other contingencies. The government should continue the holistic approach in joint risk assessment, planning, and training with the private sector. There is a need to stimulate a just-in-case business model by supporting essential service providers to stockpile reserves, shorten supply chains or create capabilities to manufacture critical inventory domestically.

[1]In 2016, NATO agreed on seven baseline requirements for national resilience against which Allies can measure their level of preparedness. These requirements reflect the core functions of continuity of government, essential services to the population and civil support to the military under the most demanding circumstances: 1) assured continuity of government and critical government services; 2) resilient energy supplies; 3) ability to deal effectively with uncontrolled movement of people; 4) resilient food and water resources; 5) ability to deal with mass casualties; 6) resilient civil communications systems; 7) resilient civil transportation systems. In 2021 NATO summit resilience was on of key deliverables focusing on societal resilience.

[2] Resilience mentioned 18x times in the Latvian State Defence Concept and 11x times in the National Security Concept.

[3] No one cannot be ready on 100 per cent, that is why the primary skill is the ability to transform, adopt.

[4] NATO: around 90 per cent of military transport for large military operations is chartered or requisitioned from the commercial sector; on average, over 30 per cent of satellite communications used for defence purposes are provided by the commercial sector; and some 75 per cent of host nation support to NATO operations is sourced from local commercial infrastructure and services.

[5] Directive proposals on the resilience of critical entities (CER directive), the Directive proposal on Network Information Systems (NIS2)

[6] ISO 22301:2019, Security and resilience – Business continuity management systems – Requirements

[7] Business continuity plan – documented procedures that guide organizations to respond, recover, resume, and restore to a pre-defined level of operation following a disruption.

[8] Government Regulation No 508 (2021) Annex 2. https://likumi.lv/ta/id/324689-kritiskas-infrastrukturas-taja-skaita-eiropas-kritiskas-infrastrukturas-apzinasanas-drosibas-pasakumu-un-darbibas-nepartrauktibas-planosanas-un-istenosanas-kartiba